Edgar Degas - Women on a Cafe Terrace in the Evening

- Alan Whittle

- 12 minutes ago

- 5 min read

Degas’s depictions of the reality of modern life were a far cry from the Salon-approved works of the period which presented viewers with grand historical or mythological subjects, formally and traditionally posed. Such academic paintings were characterised by scale and high levels of finish and detailing - the works of Ingres, whose greatest achievements had been executed earlier, in the first half of the nineteenth century, stood as paradigmatic exemplars of the standards expected by the French artistic establishment. A notable example of such sought-after characteristics would be as found in Alexandre Cabanel’s The Birth of Venus.

This was shown to great acclaim at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1863, where the classical subject matter is rendered with little or no regard to real life (to be fair, Venus is a goddess after all), but whose shimmering and porcelain-skinned figure is beautifully interpreted in the ‘grand style’. Accomplished with the finest brushstrokes, it is presented on an imperiously sized canvas – it is fully 2.5m wide. The work is also deliberately titillating to the male gaze – no wonder it was immediately snapped up by Napoleon III for his personal collection.

So, Degas’ predilection for painting ordinary people, from ballet dancers to milliners to circus performers and jockeys would have been seen as radical in such an artistic context. His ‘goddesses’ lived in the actuality of the day, not in the imagination’s fantasies. Together with his friend Manet, Degas interested himself in what was happening in the dynamism to be found closer to hand - in the workplace, the rehearsal room, and in the cafes where real life and real people lived their lives. The modern city of Paris was an exciting and vibrant place in which to live, with its recently Haussmanized streets introducing elegance, glamour and sophistication where there had once been slums, but also where all classes interacted in the concentrated pell-mell of urban life. In such a setting, the full range of human psychology would be played out and given expression through physical attitude – the particularity of posture and limb movement that expressed so much if an artist dared to look at it, recognise it and capture it boldly.

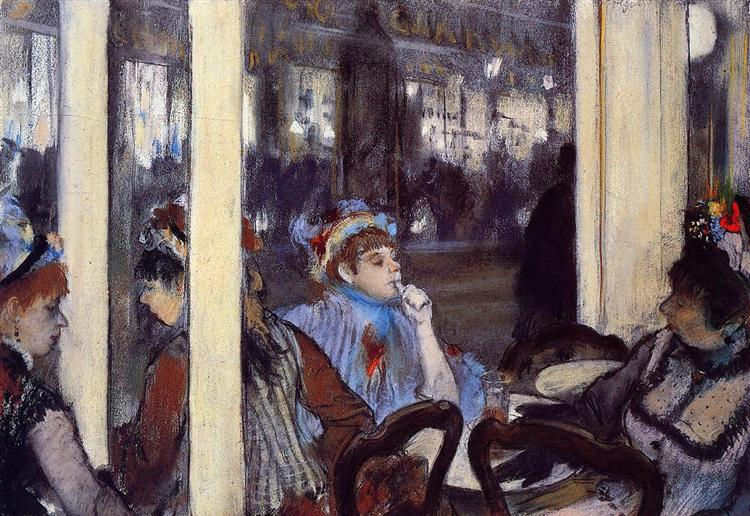

Women on a Terrace Café in the Evening represents just such a look and is striking for three reasons: its social commentary (conscious or unconscious), its unconventional composition and for its atmospheric juxtaposition of inside and outside lighting.

There are three principal female figures in the foreground, their slightly tawdry dresses, their hair styles and hats and their want of ‘respectable’ male companionship suggesting that these are prostitutes looking for business. The boulevard café terrace provided an ideal situation for these women to advertise their availability to potential customers without needing to shut themselves off indoors. Among the promenading flaneurs and badauds many prospective clients could be counted. For the price of un verre, they could loiter – their presence was not discouraged by the less decorous establishment owners who would benefit from the trade they brought in.

I think Degas was alert to the distinctiveness of the transaction-provoking behaviour that the modern urban metropolis more openly facilitated. Whether he judged it for its shame and degradation or whether he was moved simply by the unorthodox aesthetic opportunity the scene afforded is open to question. His painting L’Absinthe from a few years earlier had caused some controversy and was seen by many critics as an observation on the abject debasement, ignominy and penury that addiction to the drink could cause – there is nothing elegant or refined in the stupefied blank stare of its central female figure, nothing to suggest that her modern city life has given her anything but dependence and misery.

Commentators were shocked at its lifting the veil on the ugliness that lurked in the underbelly of their beautiful city. However, my judgement is that Degas was not motivated by a desire to condemn moral decay in society but more by the way that a physical posture and an expression could speak so eloquently about an individual disposition and more broadly about the prevalence of a state of mind.

The figure dressed in blue at the centre of the Terrace Café composition sits with her left thumb resting on her lower lip. She is facing away from the pavement and only seems to be half engaged in conversation with her table companion who seems older – it’s as if the young girl is the apprentice or novice performing under the guidance of the veteran. The thumb in mouth betokens nervousness or inexperience or at least the boredom that would accompany prolonged waiting. More insightfully, I think Degas has recognised in it a feigned nonchalance as we see the dark silhouette to her left having just passed by and seemingly having spurned her allurements. The terrace lighting has spotlit the youngster and cast the other into the shade, literally and metaphorically, notwithstanding the lurid vulgarity of her headwear confection. The artist has captured a moment of decadence, ennui, neediness and dreariness that lives in the glare of big city glamour – the contrast between the meretricious occupation and the entrancing bewitchment of capital city brilliance has been caught in this small physical motion and has become an artistic moment of insight, an emblematic epiphany.

The composition is daring too, with the strong verticals of the stanchions holding up the unseen terrace awning. These stand in counterpoint to the horizontals of the street and the pavement opposite with its ever-changing cavalcade of bustling business. But they also denote division and isolation; they imply the separateness, the otherness of these women. The columns obtrude on the view, and the artist has deliberately chosen to depict their jarring awkwardness, as if to emphasize a sense of the maladroitness of the figures they frame. These women are thereby partitioned and separated out for sale just as if they were goods in one of the grand department stores like le Grand Marché and Printemps, those newly built temples of consumerism that had begun to appear in the preceding decade.

Degas did something similar with another work in the following year, Jockeys Before the Start in which the starting pole bisects the canvas.

This seems surprising, positioned as it is not to create symmetry but imbalance. It does create a marked contrast between its own stationery stillness and the horse’s straining movement and pent-up energy, but more than that it tells us that this is a spontaneous moment and not a mannered and therefore artificial view. The pole stands where it has to stand, the artist seems to say, like it or not, and just as a photographic snapshot will sometimes show things unintentionally so this painting similarly gives us, oxymoronically, what seems like deliberate haphazardness. It impinges unapologetically as another indicator of contemporary artistic innovation, a visual break with convention.

The lighting in Terrace Café is garish and unflattering, albeit that the pastel medium and Degas’ mark-making technique lends it a degree of blurriness which is consonant with the effects of the alcohol intake of its subjects. The inside lighting is reflected outside, in the shop windows opposite where the darkness of the night is illuminated by gas lamps, some of the fifty-six thousand that lit Paris’s boulevards at the time and justifying its description as the ‘City of Light’. But this brilliance shines equally on the squalid and the smart and brings into clear view the warp and weft texture of unexceptional activity. Degas allows his eye to rest on a commonplace sordidness to which some may have preferred to turn a blind eye but which he observed unblinkingly.

Comments